The Art of Argentina

In the vast southernmost province of the country, amidst the arid canyons and dusty ravines of the Pinturas River lies the Cueva de las Manos cave complex. It’s here, on the red walls of this now almost highly deserted region that one of the finest, most intriguing and without question earliest examples of Argentinian art first came into the spotlight.

Called the ‘Cave of Hands’ in English, most visitors make the pilgrimage here to see the mysterious and awe-inspiring motifs that gave the cave its name. However, there is much more to see here than just the stencilled human hand displays that mark the interior surfaces of the cave’s largest chambers, and today the site is much-deserved to be called one of the UNESCO heritage sites of Argentina.

In fact the myriad of depictions that were discovered here represent much more than a window into Argentina’s prehistory, and definitely more than an anthropologist’s ‘dream come true’. They are not simply the utilitarian markings of unthinking tribal man; they are full of emotion and energy, loaded with cultural information, ideas and symbolism: They are art.

In fact the myriad of depictions that were discovered here represent much more than a window into Argentina’s prehistory, and definitely more than an anthropologist’s ‘dream come true’. They are not simply the utilitarian markings of unthinking tribal man; they are full of emotion and energy, loaded with cultural information, ideas and symbolism: They are art.

It should then come as no surprise that with an artistic tradition so long and intimately mixed with the country’s human history, Argentina really does pack a punch when it comes to cultural offerings in this sphere. From the 10th century BC cave decorations visible in Santa Cruz, to the modernist street art of downtown Buenos Aires, the people here have always been proudly creative and have shown no signs of slowing in their artistic output, ever.

Pre-hispanic Art

Most art historians divide the Argentinian tradition into two rather broad but helpfully distinguishing categories: Pre-hispanic and post-colonial. The former incorporates several thousands of years of artistic tradition that existed well before the borders of modern day Argentina were established on the continent. Most notably perhaps, this is where the early cave paintings of the indigenous paleolithic people of Santa Cruz and the ceramic carving traditions of the north Argentine Condorhuasi tribes are placed; representing the raw and earthy crafts techniques of most pre-European artistry here.

The second category is, predictably, much larger. It includes the multifarious traditions of Latin American art and all its sub-categories and off-shoots. These are, not surprisingly, many; such is the usual output of colonialism on displaced and identity-wary cultures.

With the sudden explosion of European cultural traditions on the continent around the late 16th century, following decades are characterised by a move towards Spanish styles and imagery. More specifically this meant religious iconography popularised by the state-funded missionary movement that had dug its claws deep into the social fabric of the Argentinian mainland.

In line with the stabilisation of Argentina as a colonial power, the domination of religious art changed slightly in the late 1700s and early 19th century. This was when Romanticism was beginning to flourish in the west, and an interest for foreign worlds far away became something of a vogue among Europeans travelling to Latin America.

Post-colonial Art

Many think that it is precisely for this reason that the earliest of truly Argentinian artists in the post-colonial tradition were concerned primarily with real-life scenes of everyday life and historically loaded portraiture that not asked for, but demanded the viewer’s attention. In 1837 Carlos Morel painted scenes depicting the national struggles of the Argentine people, and Candido Lopez determined to capture the travails of gaucho life. These were the earliest painters in the Argentinian school, the artists who set out to define and redefine their own image and identity through raw and visceral representations of the country in which they were struggling to convey.

The next major change came with the late 19th century influx of European influence here. Largely Italian in origin, painters like Eduardo Sivori (himself the son of two first-generation Genoese immigrants) helped to integrate the burgeoning influences of Italian Romanticism with the now well-established schools of Argentinian fine art. He’s now most notable for his successes in symbolism and some magnificent portraits of rural life, all of which are honoured in the Eduardo Sivori Museum in central Buenos Aires.

The next major change came with the late 19th century influx of European influence here. Largely Italian in origin, painters like Eduardo Sivori (himself the son of two first-generation Genoese immigrants) helped to integrate the burgeoning influences of Italian Romanticism with the now well-established schools of Argentinian fine art. He’s now most notable for his successes in symbolism and some magnificent portraits of rural life, all of which are honoured in the Eduardo Sivori Museum in central Buenos Aires.

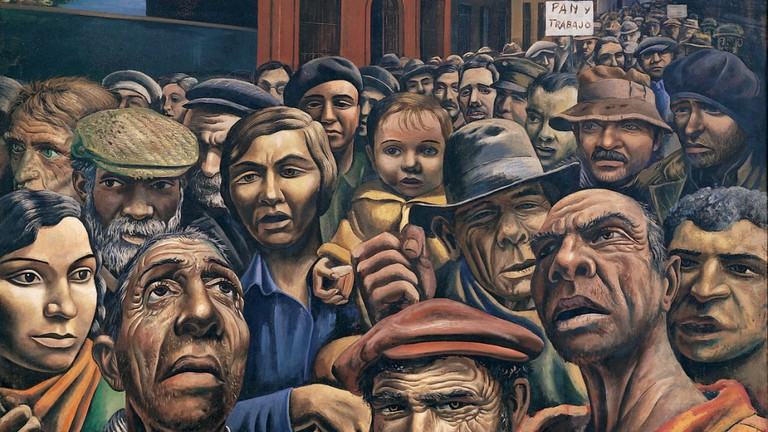

In subsequent years Argentinian art became tied up (and this is true for most things in the country) with the tumultuous political saga that was to dominate the first half of the 20th century. Groups like the Boedo painters took the proverbial ‘bull by the horns’ and dealt with social injustice issues head on, while others harked back to the traditional symbolism of Argentina’s yesteryear and waited for the dust to settle.

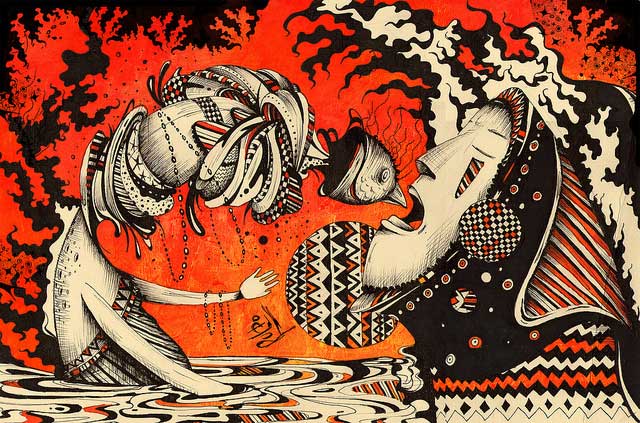

Today Argentina is alive with modern art that’s a curious and almost indefinable mix of new-age traditions. From surrealism to eco-sculpture, the cultural directions here change rapidly, and there’s no sign of the energy that has informed this country’s creative character for so long of letting up any time soon.

Today Argentina is alive with modern art that’s a curious and almost indefinable mix of new-age traditions. From surrealism to eco-sculpture, the cultural directions here change rapidly, and there’s no sign of the energy that has informed this country’s creative character for so long of letting up any time soon.